Syed Sheharyar Ali is now the fourth generation of his family to be a major business owner in the region that is now Pakistan, and fifth if you count his great-great grandfather Syed Wazir Ali. Conventional wisdom dictates that the family business would at the very least have been in severe decline by now, if not outright bankrupt. But Sheharyar, an executive director and heir apparent at the Treet Corporation, and his father Syed Shahid Ali, the CEO of Treet, appear to have the kind of zeal to grow their family business one rarely finds among men who have grown up with generations of wealth in their family’s past.

Indeed, the company’s leadership may be overdoing their attempts to ward off the decline that typically set in for family businesses by this stage in their life cycle. At its core, their growth strategy relies on investing in what appear to be several high growth businesses that have almost nothing in common with each other. If they succeed, they may well build one of Pakistan’s most successful and dynamic diversified conglomerates. Yet the diversity of the businesses they are seeking to expand into may yet prove the group’s undoing if they are not careful.

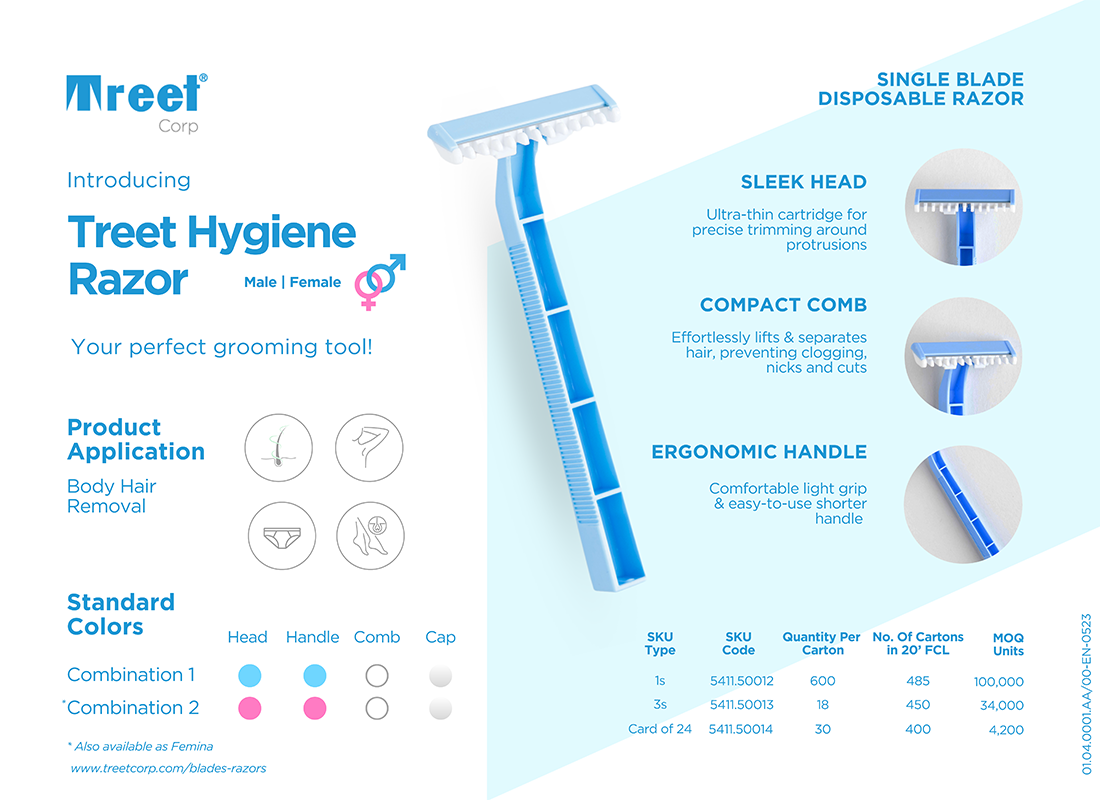

Treet is Pakistan’s leading manufacturer of razor blades for men’s shaving products, besting the global leader Gillette by a wide margin in terms of market share within the country (85% to 5%, according to estimates by the Treet management). And yet, over the past decade, and continuing into the coming years, the company has gone on a diversification kick the likes of which are almost unprecedented in corporate Pakistan.

Treet is now involved in everything from its core business of razor blade manufacturing to motorcycle assembly, manufacturing batteries that can be used in cars as well as backup storage for solar power, and higher education. And that does not include their venture capital investments in companies that range in product offering from artificial intelligence, the internet of things (IoT), to e-commerce.

Will this gamble work? The company’s history and management structure suggest at least some room for optimism, though there does not appear to be precedence for the level of complexity the current management has taken on for themselves.

The other branch of Syed Maratib Ali’s empire

Treet Corporation’s genesis lies in the industrial empire whose origins trace back to the peak of British rule over South Asia.

Syed Maratib Ali was a highly successful entrepreneur in the early part of the twentieth century and made his fortune supplying a variety of goods to the British government in India, specifically the British Indian Army. He followed in the footsteps of his father, Syed Wazir Ali, who had initially started a canteen that served troops in the British Indian Army, a business that gradually morphed into Wazir Ali Industries. “In the early 1900s, we caught a decent break, and at one point were managing 10 of [the Royal British] regiments,” said Sheharyar, in an interview with Profit.

As the business continued to grow, Sheharyar claims that the family decided to hold off on further expansion as independence continued to grow closer, supposedly with the intention of supplying the Pakistan Army if Partition were to go through. “My family was in favour of the Partition and we also contributed towards attaining it in many ways,” said Sheharyar.

Maratib’s three sons – Amjad, Wajid, and Babar – leveraged their father’s financial success to become highly successful individuals in their own right. Amjad, the eldest, became involved in politics. He served as the chief whip of the ruling Unionist Party in the Punjab Assembly from 1940 to 1945, and in 1946 he was elected to the Constituent Assembly of India. After Partition, he went on to become Pakistan’s ambassador to the United States (1953-55), Federal Finance Minister (1955-58), and ambassador to the United Nations (1964-67).

Wajid and Babar decided to stay in the family business. While Wajid and Babar were both involved in the Packages Group, as both the business and family expanded, over time the shareholding between the two brothers and their descendants has diverged somewhat, with the Packages Group having a larger (but not exclusive) shareholding held by Babar and his children, and the Treet Group having a larger shareholding belonging to Wajid’s children and grandchildren. (We have previously covered the history of the Packages Group in an earlier article).

While the Packages Group is clearly the larger of the two, the Wajid Ali side of the family has a sizeable business of their own in Treet Corporation and Loads Ltd, both of which are publicly listed companies that each owns several subsidiaries.

Loads Ltd is an automobile parts manufacturer that makes radiators, exhaust systems and other parts for both car and motorcycle assemblers in Pakistan. Treat Corporation, the larger of the two, has several business lines, almost none of which has anything to do with any of the others.

Razor blades – the core business

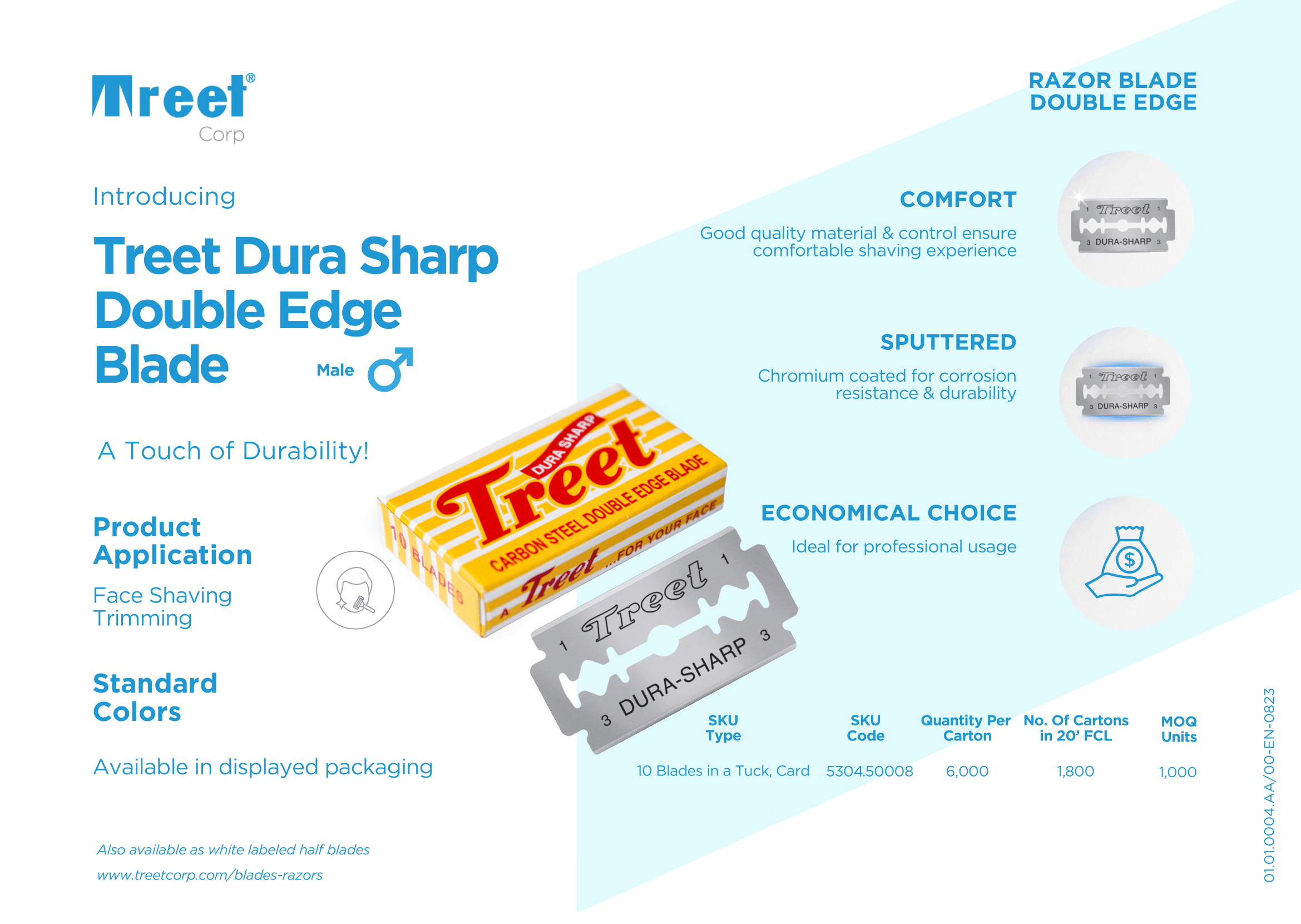

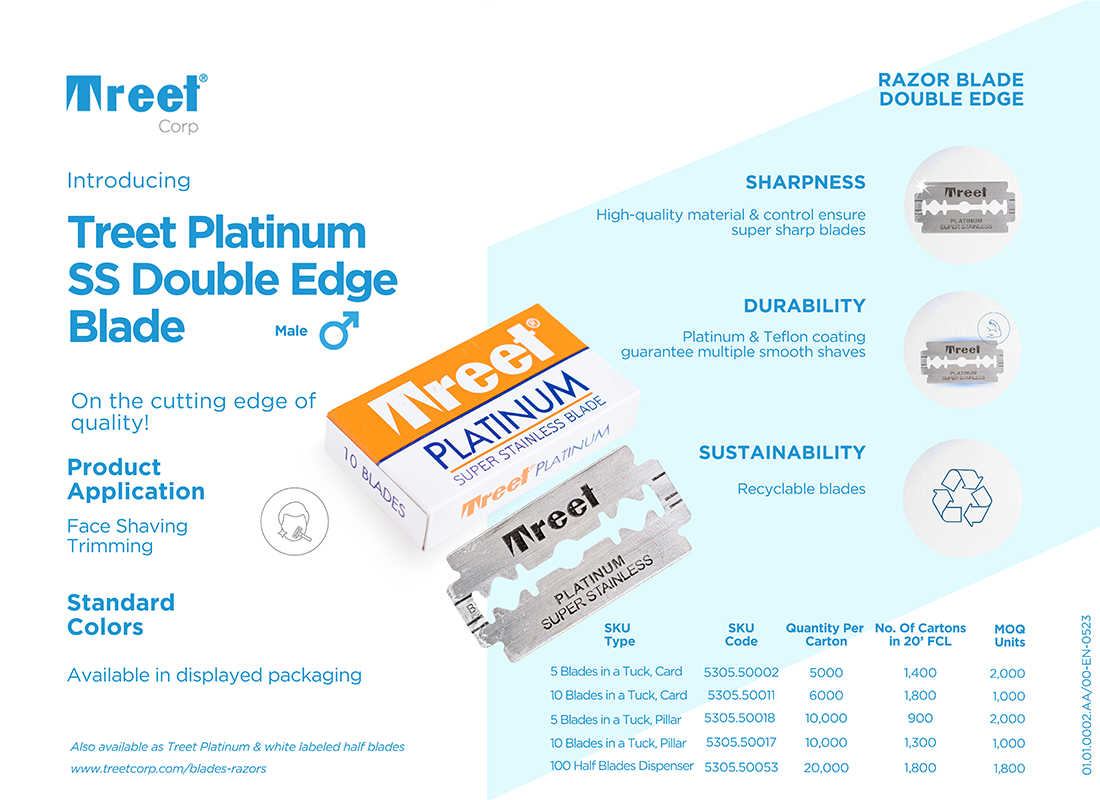

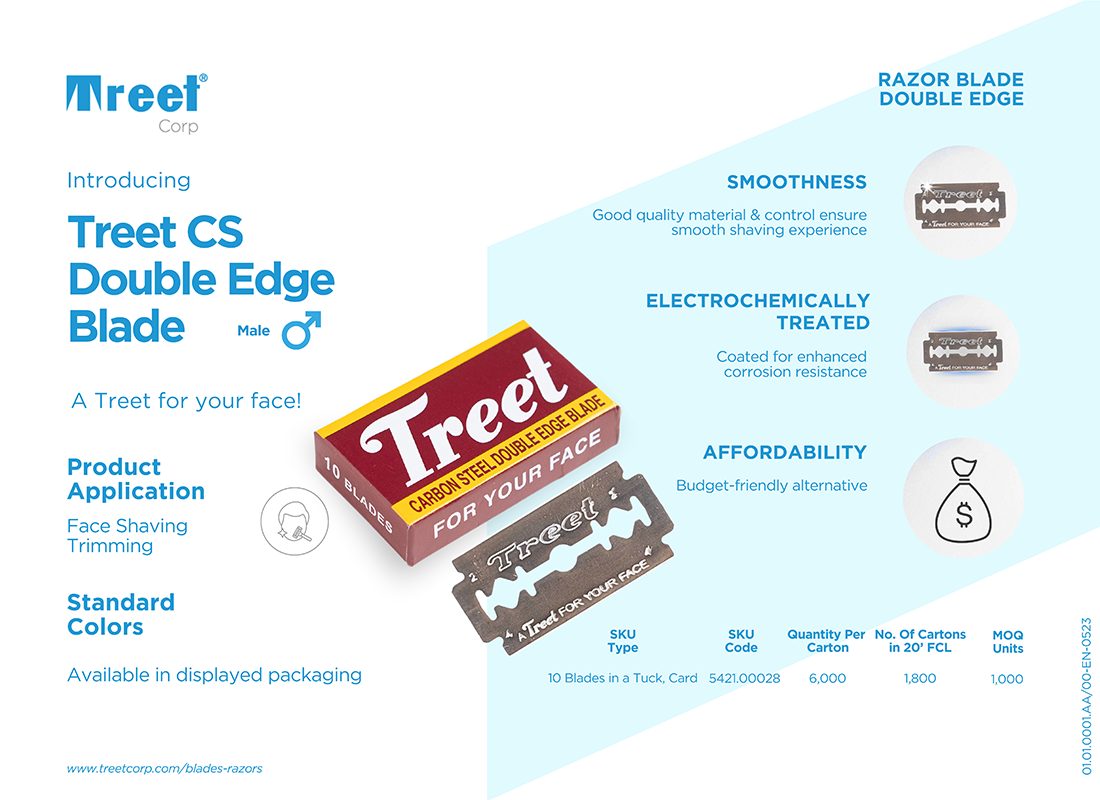

The blade business is the oldest – and by far the largest – part of the Treet Corporation’s business, accounting for Rs5.4 billion (63.6%) of the company’s total revenues of Rs8.4 billion for the financial year ending June 30, 2017. The Treet brand of blades is by far the best-selling blade in Pakistan.

“The packaging is for the masses – as are the blades,” said Sheharyar. “We don’t pitch for niche markets, as our family strategy has always been to go after the mass market. The issue with niche markets is that there is always going to be somebody who is going to make something better or something cheaper. So instead of focusing at that, we concentrate on the mass market where, even if competition comes, there is a lot to share.”

With regard to the competition, Ali said: “That Gillette leads the market here is a major misconception. In reality, they don’t even control 5% of the Pakistani market. Gillette was manufacturing here some time ago but they shut down [the manufacturing plant] because they couldn’t compete. Besides Gillette only targets the ‘A’ class [of consumers], but that’s not the majority of Pakistani population and not our market, so Gillette is not even our competitor.”

That said, to him, Gillette remains an inimitable brand. “They spent over $2 billion just to develop the Gillette Mach 3. We are at number two when it comes to quality but we don’t aim to compete with Gillette anyway.”

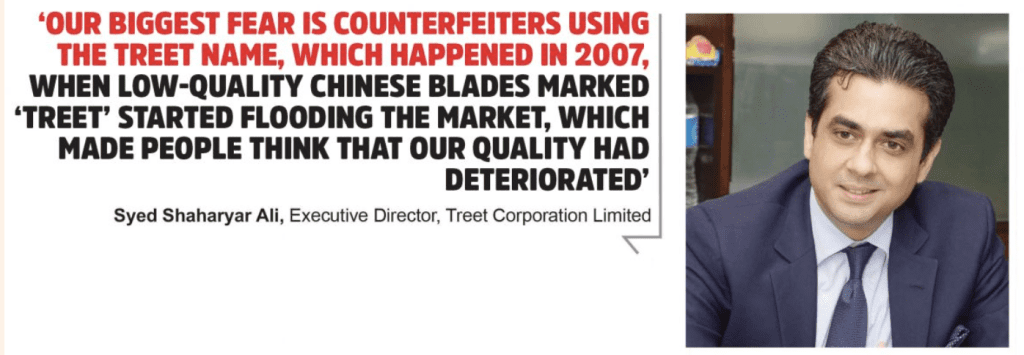

To him, the main competition to Treet blades comes from India, Turkey, China and the brands operating in and around Pakistan. “New brands keep coming, but our major strength is the barber segment and that remains intact. Our biggest fear is counterfeiters using the Treet name, which happened in 2007, when low-quality Chinese blades marked ‘Treet’ started flooding the market, which made people think that our quality had deteriorated. It took away 50% of our sales and that was the only time in 70 years that we felt scared.” To maintain quality control, and to be able to detect counterfeiting, Ali said that the company now has an extremely detailed record of its production, distribution and sales. “Of the 1.5 billion blades produced every year, you give me one packet and I can trace where they were produced, who the distributor was, and where it was sold.”

A key problem for the company in terms of production is the fact that it is not able to rely on locally produced steel to manufacture its blades and has to import them. “No Pakistan steel mill produces the sort of quality needed for manufacturing blades. So, our cost is very high.” He does not expect this challenge to disappear any time soon, even with new steel mills coming online. “We would try to come up with some sort of an agreement with the new steel mills that are being set up, but the steel needed for shaving blades is very specialised. And it’s going to take them a long time to develop something that fine. There is no room for any inconsistency in the blade, it has to be completely smooth, which means the steel has to be at par with that sort of quality as well.”

The other businesses: soap, packaging, motorcycles, and pharmaceuticals

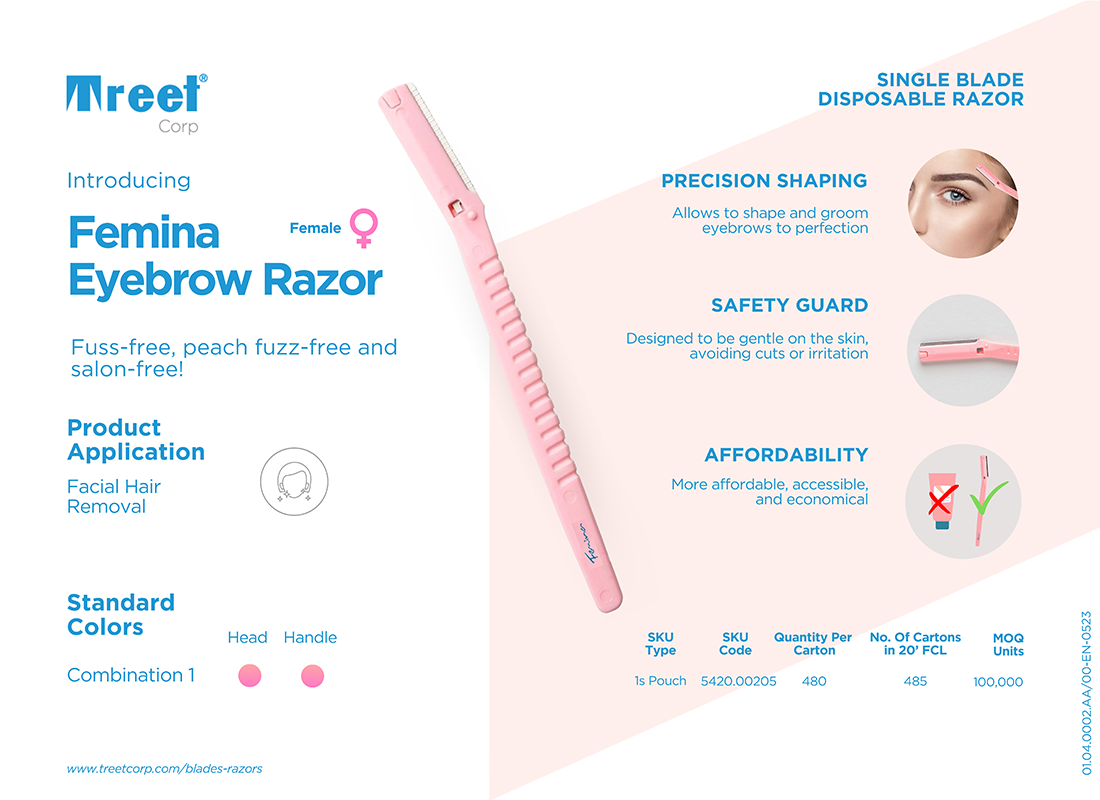

In addition to the blades business, Treet is a manufacturer of soap, corrugated boxes, and is also engaged in motorcycle assembly. While soap manufacturing has been a long-time business of Treet corporation (the company owns the low-end “Saba” brand of soap), and is at least related to blades in that both are products involved in grooming, the foray into packaging, motorcycles, as well as the other businesses that started last year, happened after Sheharyar joined his father at their business in 2007 and began aggressively pursuing a strategy of diversification.

“Treet was a neglected company,” says Sheharyar. “We had other businesses. We have been here for a very long time and we are the only blade manufacturers in Pakistan. And yet we didn’t grow as much as we should have.”

The first business Sheharyar decided to expand into was arguably the worst idea he has had so far: motorcycle assembly. This was a venture that has no chance of making a dent in the Pakistani market for two-wheeler automobiles.

Here is why. While Pakistan has dozens of motorcycle brands, and the country regularly sees sales in excess of 2 million motorcycles a year, the market is dominated by one company – Atlas Honda – which makes a motorcycle that is the dominant brand (over 50% market share) and also the most expensive brand of motorcycle you can buy! If over half of customers in a market look at your product, and look at one that is sometimes as much as twice as expensive and still say “I want the Honda”, what chance have you got to make inroads? In what universe are you going to beat that product?

You would have to engage in a completely game-changing strategy that fundamentally transforms the nature of the industry, and judging by the fact that, five years on, Treet still only sells Rs322 million worth of motorcycles a year, the company does not have that kind of commitment to the motorcycle business.

Nor could it possibly have that kind of commitment to any other business, given how many ventures the company has decided to deploy capital into. For instance, while the packaging business of manufacturing corrugated boxes has been around since 2005, the company does not appear to be interested in expanding it at all, using the subsidiary that is incorporated to engage in that business – the publicly listed First Treet Manufacturing Modaraba – to also become the vehicle that manages the group’s foray into battery manufacturing.

The battery manufacturing idea

Of the many lines of business Treet has started, the one that appears to have gotten the most attention – both in terms of management focus as well as capital – is the new battery manufacturing business. For this business, the company has invested in a 40-acre, Rs6.25 billion manufacturing facility in an industrial estate in Faisalabad.

The company has signed an agreement with South Korean conglomerate Daewoo to manufacture maintenance-free batteries, also known as valve-regulated lead acid batteries. The batteries do require some maintenance, but are generally easier to manage than conventional batteries. Crucially, their biggest feature is that they can store nearly as much energy as a lithium-ion battery, but are significantly cheaper to manufacture.

This feature is especially important in Pakistan, where power outages are still common, and many middle class consumers – in both urban and rural areas – install uninterrupted power supply (UPS) systems in their homes, which rely on lead-acid batteries as the storage capacity.

In an interview with Business Recorder in September 2017, Ali Aslam, the chief operating officer (COO) of the Treet Battery Project identified why the company believed that the UPS market will be a crucial one for the company. “As long as load-shedding is not completely eliminated, there will be a need for backup power. So even if load-shedding comes down to 2-3 hours in a day, the demand for batteries will still be there,” he said.

But more importantly, he highlighted what is potentially an even bigger end market: the energy storage capacity for the increasingly large number of homes in Pakistan that now have solar panels installed on their rooftops. “You have to also realise that solar power is developing very rapidly with an ever declining cost structure and an improved back-up service,” said Aslam. “Our projections for solar based electricity generation are extremely positive. Therefore, even when UPS sales might decline if load-shedding is eliminated, we expect solar energy to continue with its rapid expansion in the future.”

Rapid expansion may be a bit of an understatement. Since Pakistan does not have any manufacturing capacity for photovoltaic cells, all solar panels in Pakistan are imported. In fiscal year 2003, the country imported $0.2 million worth of solar panels. In fiscal 2017, that number was an astonishing $722 million (Rs75.5 billion). That comes to an average annual growth rate of nearly 79% per year. In the last five years, Pakistan has imported $1.8 billion worth of solar panels. Providing the energy storage for all of those panels could become a lucrative business and it looks like the Treet management has had the foresight to invest in that capacity earlier than their competitors.

The Treet battery plant is aiming to produce up to 1.5 million batteries in their first phase of production, though they will have an installed capacity for producing 5 million batteries a year. Trial production has already begun at the Faisalabad plant and commercial production is expected to begin before the end of March 2018.

The venture capital business

In addition to all of these – and other – businesses that are housed within the company (we have not even described the company’s foray into higher education), Treet also acts as a venture capital investor, and has invested in several promising startups.

In early 2017, Treet Corporation invested $150,000 (Rs16.5 million) in Car Chabi, a Lahore-based startup which provides a digital key to cars using smartphones. At the time of this investment, Sheharyar said: “Automation is the future and Pakistan still has a long way to go. Car Chabi will get the first mover advantage.”

Later in the same year, he invested in two more startups. The first of these was Grocerapp, an e-commerce company that seeks to make grocery shopping in Pakistan migrate online. Sheharyar invested Rs10 million for 17% of the equity, which valued the company at just under Rs60 million, or 2.5 times their sales.

The second startup was Dataspine, a company that dabbles in the intersection between cloud computing and artificial intelligence, and is building a platform that can be deployed as a service on any cloud or on-premises enabling data science and engineering teams to seamlessly build, deploy, monitor and scale their models and production pipelines using their existing tools and workflows – without the in-house technical debt and operations overhead. Sheharyar teamed up with a friend to invest Rs10 million in Dataspine, in exchange for a safe note.

The pharmaceutical business

And in January 2017, Treet bought a 58% stake in Renacon Pharma, a small pharmaceutical company that produces hemodialysis concentrates in Pakistan. The concentrate is used to make dialysis fluids, which consists of water, glucose, and electrolytes in quantities that closely resemble that which naturally occur in blood. It is used by dialysis patients who suffer from kidney failure. An estimated 40,000 people in Pakistan are diagnosed with kidney failure each year, and each of these people need to get hemodialysis three times a week in order to be able to survive.

Renacon had sales of just over Rs310 million in fiscal 2017, a growth of 14% over the previous fiscal year. Crucially from the perspective of investors, Treet Corporation plans to list the company publicly in April 2018.

“The mandate has already been given to Arif Habib and BMA Capital,” said Sheharyar. “Hopefully by April we would have the book-building process for Renacon. We are using the IPO proceeds to not only expanding the current production capacity but also diversifying into other concentric areas. We have acquired land in Faisalabad Industrial City for our diversification/expansion plan.”

How is the business doing?

If that list of businesses was exhausting to read, one can only imagine how exhausting it must be to actually run all of those ventures. It is clear from the lack of connection between most of those enterprises that some of them are going to succeed, but most will likely fail and should probably be shut down before they take up too much of the management’s energy and the shareholders’ capital.

But Treet as a whole appears to be growing at a reasonable pace. Revenues for the twelve months ending September 30, 2017 (the latest for which financial information is available) clocked in at Rs8,714 million. Since fiscal 2006, that number has been growing at an average of 18.8% per year – a respectable percentage, indeed. However, all of the management attention that has gone into businesses that have no ability to scale due to a lack of attention and capital means that operating costs have grown faster than revenues, and hence net income has grown by a much slower average of 7.1% per year during that same period.

Nonetheless, it appears that in the battery project, Treet has finally found the one big winner that they have been looking for to seal their fate as a fast-growing conglomerate in Pakistan. It is not yet clear if that venture will succeed, and there is certainly stiff competition in the battery space from more well-established players, but if Treet is able to sell anywhere near the number of batteries they will have the capacity to produce, the company will likely grow exponentially.

If only the family that owns Treet can focus on their most promising businesses, and not try to do everything all at once, Treet Corporation may well become a conglomerate to be reckoned with in Corporate Pakistan.