Albert Einstein defined insanity as doing the same thing over and over again, and expecting different results. He would probably be rolling in his grave if he saw Pakistan’s innumerable attempts at trying to domestically build internal combustion engines for vehicles. However, while the automotive industry persists in its continued attempts to do so, two interesting things have happened this month.

Firstly, the China-Pakistan Joint Research Centre on Earth Sciences has signed an agreement with China’s Tianqi Lithium to explore Pakistan for lithium deposits this Friday. What is the significance of this? There’s likely lithium abound. Why is that important? Lithium is one of the key ingredients in the manufacturing of electric vehicle batteries. What does this mean? Nothing really, because we are most likely not going to utilise it in any meaningful capacity. Why do we say this? Because of the second interesting thing that has happened in the

industry this month.

Haval has unveiled Pakistan’s first hybrid-electric vehicle. A full 24 years after Toyota unveiled the world’s first hybrid, the Prius, in 1997. Now, kudos to Haval for achieving what no other company could in Pakistan but we have a problem. If we are just not producing hybrids, then we are not going to produce electric vehicles anytime soon. This subsequently means we are not going to produce electric batteries and are going to miss out on the next big thing globally, similar to how we missed out on the internal combustion engine entirely. In an attempt to avert shooting ourselves in the foot, Profit suggests we actually try to export them by utilising the export processing zones. Remember those, anyone? Doing so would allow us to get on the bandwagon for the next big thing in the industry globally whilst our local sector continues to live out its hybrid escapades.

Now Profit may have picked fighting words, but hear us out. Firstly, let us explain the significant and interrelatedness of the aforementioned two events.

Looking at what we are about to squander and why?

Profit talked to a source at the Geological Survey of Pakistan, who on the condition of being anonymous, did tell us that there were various sites that had been identified with potential lithium reserves. Profit also reached out, persistently might we add, to Ahsan Iqbal, the Federal Minister of Planning & Special Initiatives. Sadly, we could not obtain a comment. Thankfully, his rejection indicates that there may actually be fire to the smoke because a flat rejection is very easy to give. More importantly, Pakistan has been touted to have lithium reserves as far back as 2005 based on a report by the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics.

These reserves were touted to be in Chitral and in Gilgit-Baltistan, but we just never got around to exploring them. Why? A mixture of a lack of finances and aforementioned areas being subject to an insurgency movement not too long ago. Most importantly, these areas in Pakistan are not random places on the map by any means. They, alongside Afghanistan, are part of the Kafiristan Valley. What is the importance of this? Afghanistan is projected to have the largest lithium deposits in the world. And where in Afghanistan are they? Afghanistan’s Nuristan

province is touted as one potential destination. It also borders Chitral and Gilgit-Baltistan, and thus we come full circle. So let us tell you why Pakistan will squander this entirely.

Haval, Pakistan’s most technologically advanced company as of right now, chose to build a hybrid electric vehicle rather than an electric vehicle. This is very important, and very concerning. Why do we say this? Because Sazgar, Haval’s parent in Pakistan, does have access to electric vehicles through its arrangements with China’s Haval and BAIC. Yet, they chose not to. Why? “Pakistan is currently not ready for an electric car but it is ready for a hybrid electric one.” Ammar Hameed, Director at Sazgar Engineering Works, told Profit. Now why does Hameed believe that to be the case?

“Electric vehicles are not possible in Pakistan because you need to first install charging points across the country. It’s currently not feasible to own an electric car. They are good for driving within a city but you would find it hard to travel for example from Lahore to Islamabad. They are adding charging stations on the motorway but you will have a shortage of chargers as more EVs come on the road,” Hameed told Profit.

“You’ll have to wait half an hour to charge your car. Even with a supercharger, it will take 15-20 minutes to charge. Now imagine there are only two chargers on the motorway and you have four to five cars that need to be charged.” Hameed continued. He is not alone in his concerns.

“People do not have the assurance e.g. when I go as a consumer to buy a vehicle, I would like to go from here to Islamabad to Multan to Bahawalpur in one go,” Dr Naveed Arshad, Associate Professor at LUMS told Profit. What does this lack of assurance mean? It means lower potential sales. What do fewer sales mean? Fewer companies want to actually launch electric vehicles. Now what is the importance of this, apart from wanting to find a more affordable alternative to the E-Tron? Lack of interest from the government, and likely subsequent governments to come. Profit understands that this is a sweeping statement so, therefore, let’s contextualise it by explaining how the State approaches industrial policy.

So why don’t we have internal combustion engines? “Engines are made at a certain volume based on techno financial feasibility and not a wish list. If a car has a volume of 5,000 then making an engine for it is not feasible,” Asim Ayaz, General Manager of Policy at the Engineering Development Board, explained to Profit. Seems simple, right? Well, this applies to electric vehicles, and more importantly the batteries in them as well. “Electric batteries cannot be made from the outset. You will need to manufacture electric vehicles first. Once production for them starts, and you have an established market for them then you will see batteries and other components being built here,” Ayaz continued. Do you see how all of this tied together, and why it is concerning? Let’s up the ante and make it scarier.

It is unfair to criticise Sazgar for doing what they did, rather than what they could have done because of how new they are to the market. They too need some pre-established volume to take a plunge on electric vehicles. What about placing our bets on the established triad of Toyota-Honda-Suzuki? That is a very bad idea, and it also explains how bad the situation is.

“All three of them are the furthest behind in the electric vehicle race. Toyota does not have an electric vehicle to offer except in China. Honda does not have an electric vehicle to offer except in China and one model in Europe that they have just introduced. Suzuki does not have an electric vehicle at all,” Naveed told Profit. So the gist of the matter is, companies that have the volume to potentially make batteries do not have the technology, and the ones that have the technology do not have the volume to make it feasible.

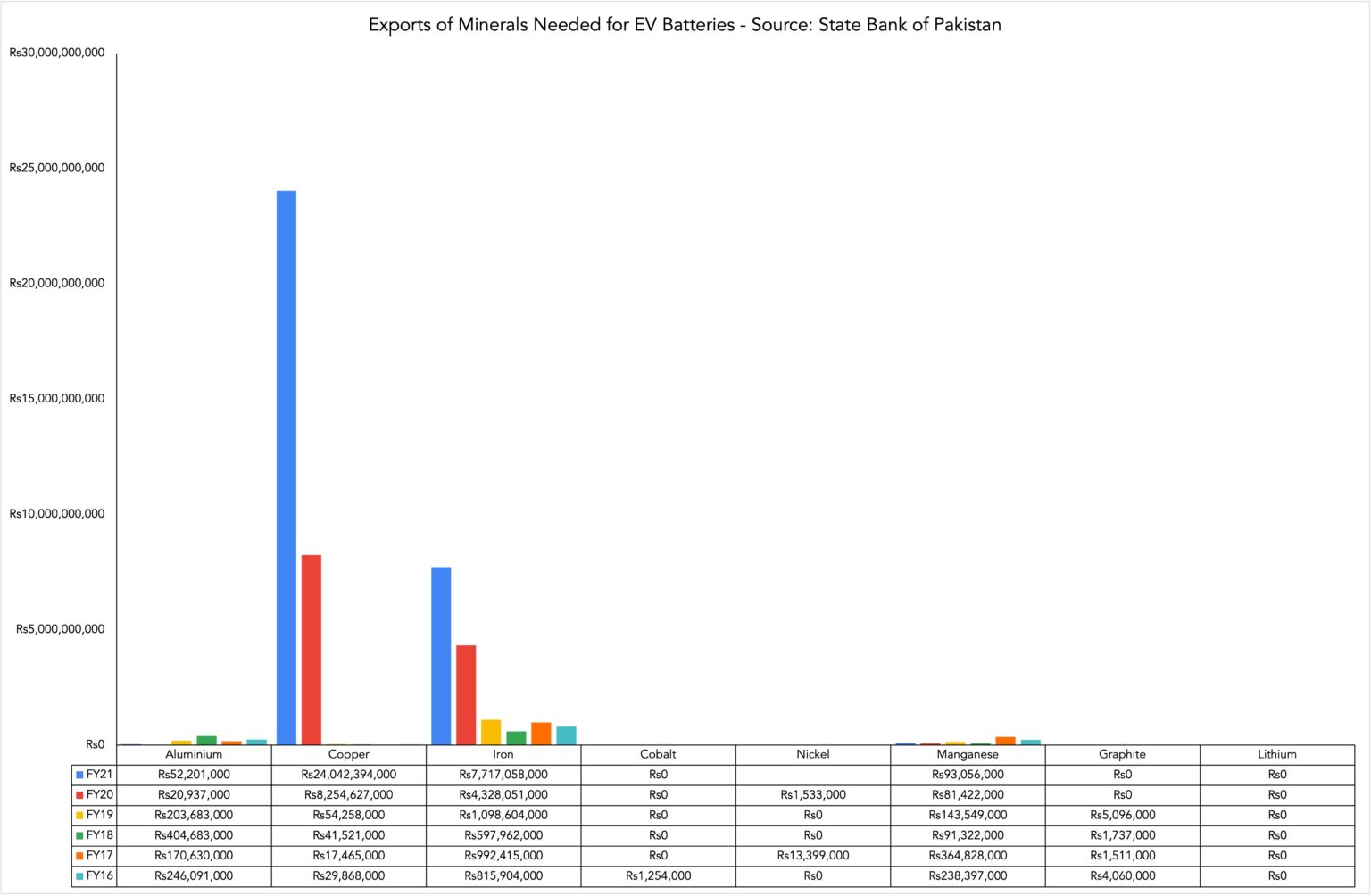

In this game of solving the chicken and egg problem, Pakistan will squander its lithium. Why, you ask? Let us explain. Electric vehicle batteries are a mix of base metals such as aluminium, copper, and iron, precious metals such as cobalt, nickel and manganese, finally and elements such as graphite and lithium. Now where Pakistan has not had lithium, it has had all other elements. Firstly, disclaimer, for whatever reason, there is no one database for all of Pakistan’s mineral reserves. However, the State Bank of Pakistan does track the raw materials

that Pakistan exports. Interestingly we export aluminium, copper, iron, cobalt, nickel, manganese, and graphite.

Pakistan has exported all aforementioned minerals in some capacity between FY 2016 and FY 2021. We recognise that exporting minerals does not necessarily equate to total available reserves. However, if a material is being exported, then there is a reserve of it. It is also likely that this reserve might be very large because why else would you export something if you did not have it in amounts exceeding its domestic requirement? That too in a country with chronic balance of payment deficits?

Now, on the chance that we have no lithium reserves, Pakistan has had enough of a cocktail of minerals to actually build electric vehicle batteries. We had to just import lithium, and we somehow managed to not draft an agreement with the world’s largest source of it which just so happens to be our cash-strapped neighbour. Do you see why Profit is concerned? Our obsession with the domestic manufacturing centred upon the local market is basically unrequited love. What a therapist would refer to as Stockholm Syndrome, Pakistani decision makers have forever, whether consciously or unconsciously, referred to as our localisation and industrial policies.

The question that now begs answering, and rightfully so, is can we even make an electric vehicle battery that the world will want to buy from us? Particularly given that we have, until now, done a very good job at highlighting our lack of ability for industrial policy. And how exactly would Pakistan be able to export a product without selling it to the domestic market? We’ll get to all of this. But first, let’s look at what we will be missing out on if we continue with our current trajectory.

What is the size of the pie?

The size of the pie that we are not looking at actively forsaking to be precise.

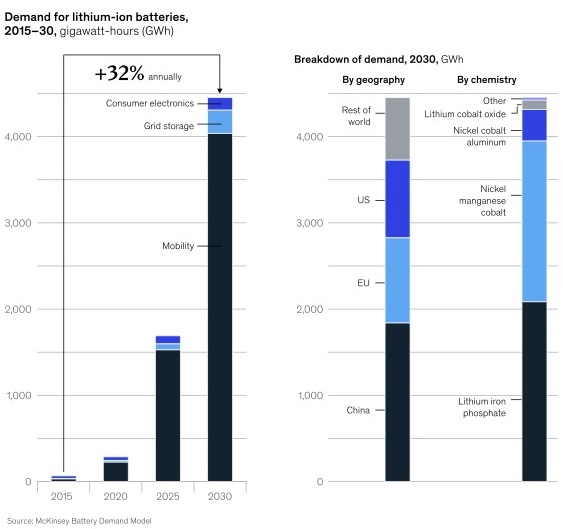

Global demand for electric vehicle (EV) batteries will increase 30% by 2030, whereas the global value chain will increase 10 times to reach $410 billion over the same period. Furthermore, the number of electric cars on the world’s roads by the end of 2021 was about 16.5 million. This number is set to increase manifold to 350 million electric vehicles by 2030. In contrast, Pakistan has next to nothing.

To be precise we had almost 2,000 all-electric passenger cars in August 2021. Future growth is likely to not be as rapid as the global average as the government has deemed it necessary to stamp duties on electric vehicles to curb their import. This is on top of the aforementioned attitude that automotive companies already have. How much could Pakistan’s market potentially grow to? Well, until August 2021, Pakistan had a total of four million passenger cars. That is all cars on the road.

“Furthermore, on the topic of just exports. India and China, our neighbours, are also projected to be key consumers of electric vehicles. How much will our neighbours be consuming? There’s no officially agreed upon metric yet. However, Ghias Khan,Chief Executive Officer of Engro Corporation, puts the number at 50% of all global vehicles.

“The market is huge. There is global demand for this and a global shortfall. The shortfall is so tremendous that no one country can fulfil demand so this has to be a global effort. When there is a global effort, then that automatically means a — blessing in disguise for countries like Pakistan where the cost of production is low,” Sohaib Chaudhry, Group Head Innovation at Treet Corporation, told Profit. He added that this will be a very lucrative business in the next 10 years. We should probably manufacture them and export, right? Now Profit will hammer along this point but actually manufacturing and exporting them is easier said than done.

“The challenge is that battery manufacturers in Pakistan are focused on lead-acid batteries: The ones in used cars and UPS, they are not suitable for electric mobility and for long duration applications. Technologies like lithium-ion and other chemistries of lithium are needed for electric mobility. That manufacturing base does not exist in Pakistan,” Dr. Arshad told Profit. So, can we make them then?”

“Can we actually make something to export?

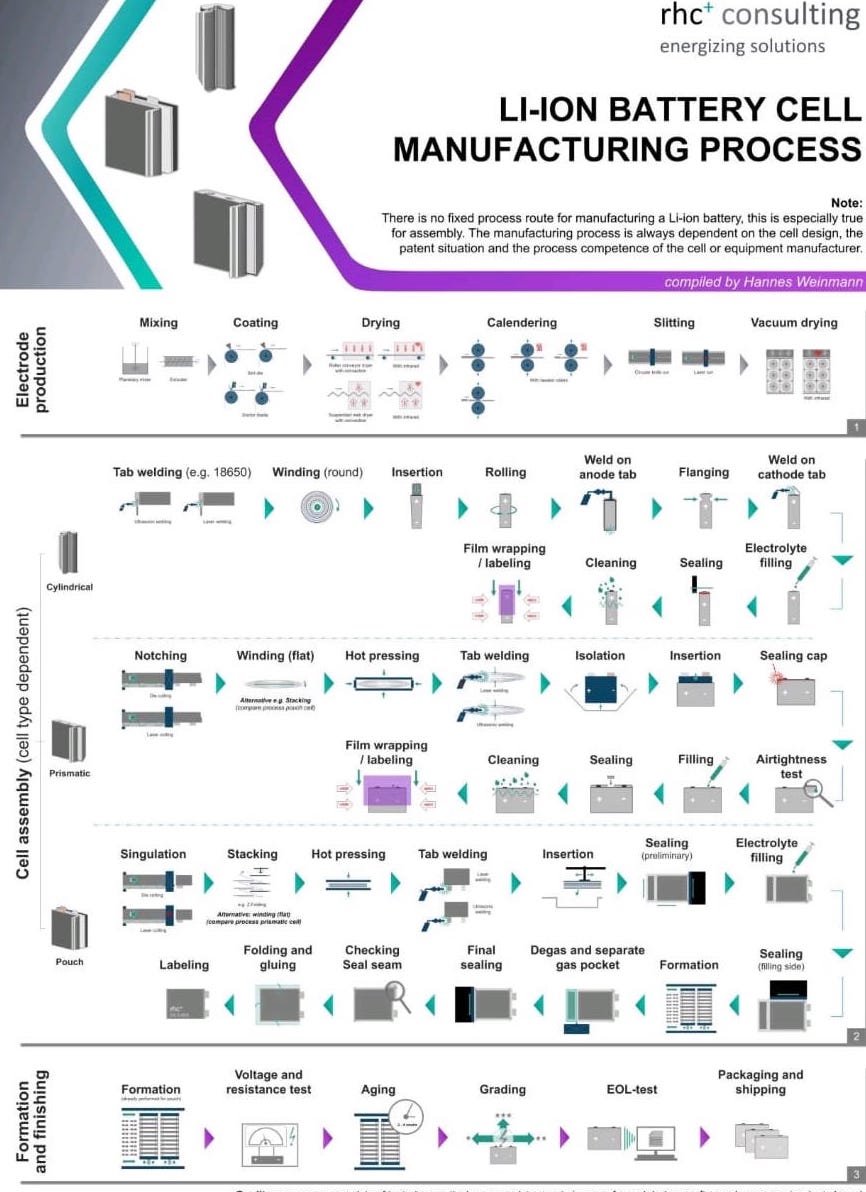

“Maybe. Firstly, there are different kinds of EV batteries. Layers to be more precise. EV battery manufacturing is a three tier process. In the first tier you are manufacturing special materials required for the battery, in the second tier you are assembling the battery cells, and in the third tier you are assembling the battery packs.” Chaudhry told Profit.

What is the relevance of this?

“The lowest tier is a low-hanging fruit. You can utilise it for both exports and the local market. You can import the EV cells depending upon the type you need, for two, three or four wheelers, and then you can assemble the battery packs in Pakistan,” Chaudhry told Profit.

Now Chaudhry mentions both the export and local market. This is important. Why?

Because that is how Pakistan will enter based on current technical capabilities. Unless Pakistan manages to leapfrog its contemporaries in the next few years, it will almost always enter this particular stage in the sector whenever it does decide to take the plunge. This is also where we will see history repeat itself if it opts for its current practices rather than go for exports.

What will happen whenever Pakistani companies decide to enter the electric vehicle battery industry? They will be in a race to the bottom in terms of their margins and the prices they charge.

“The margins will be very low. The intellectual property (IP) with the batteries is mostly on the software side. I would say 40-50% of the battery’s IP is the software.” Arshad told Profit when asked about the viability of companies establishing assembly plants in Pakistan. “The margins will be extremely small so you will have to go on a larger volume and you cannot achieve that until you engage in value addition with the battery. It’s a chicken and egg problem.” Arshad continued.

“So, what is the software that’s been mentioned? It adds to the value of the product, but do we need it? And if we do, can we make it? “Lithium-ion batteries are all software controlled. They have sophisticated softwares as well as power electronics which control the battery. The problem is that most of the companies do not have the expertise to develop that kind of a battery management solution or power electronics. That is why they are always dependent on international companies for licensing or manufacturing,” stated Arshad.

However, continued abstinence from the sector in any meaningful capacity also reduces the likelihood of ancillary industries being built to support the main task.

“The ecosystem or technology for this ecosystem is mostly centred in Germany, China, and some other European countries. You will have to import the machinery and everything from there.” Chaudhry explained. Now abstinence may bring down the cost of these inputs in the long-run as they mature and their international prices drop. However, as of right now there are no examples of Pakistan leapfrogging ahead of countries in different sectors by just waiting on for a sector to mature so that the imported inputs fall in price. Our best performing sector actually tells us the opposite story.

“Look at the scale of our textile industry. It’s our biggest exporter. It operates with state of the art machinery. Brand new, all of it,” said Chaudhry. Furthermore, it’s not like these imported inputs cannot not be made more affordable for companies. So, is there a way currently available to companies that might want to set up shop? According to Ayaz, yes there is “We have export processing zones. Anyone can set up a factory to export products and all the inputs that need to be imported will be duty free.” Ayaz’s statement is in reference to Rule 14 of the Export Processing Rules (1981) which grants duty exemptions for imports from abroad and from domestic companies outside of the Zone.”

“Until Pakistan manages to find a way to develop the requisite technical capability for the advanced software and either domestically create the ancillary ecosystem or import the infrastructure affordably, it will always exclusively have to go for volume. The export processing zones assist with the volume particularly keeping the aforementioned disparity in current and future growth between the international and domestic market in mind. Catering to a domestic to largely pull all of this off in the future will be a Herculean challenge, that is only made worse by looking at the industry’s track record.

That is not to say that this disparity is always harmful. Whereas looking at the car industry does nothing but make one despair, other sectors in the economy might actually benefit from this endeavour.”

“Killing two birds with one slightly split stone”

“It is nearly impossible to completely separate the domestic and export markets of a product for one another. There will be interaction at some level. Pakistan serendipitously finds itself in an interesting position. For whichever of the aforementioned reasons, the domestic car industry does not have an appetite for electric mobility.”

However, that’s not to say other sectors feel similarly. Which sectors are we talking about?

“There are two spaces in the domestic market. Telecom towers, and the two- and three-wheel automotive segment,” stated Chaudhry. In regards to the former, “They are already running on lead-acid but some have switched to secondhand lithium-ion batteries for backup storage. It’s like the generators that are already in the towers.” said Chaudhry. Whereas in regards to the latter, “the two- and three-wheeler market will become quite developed in four to five years time. A few odd manufacturers in the EV space in Pakistan do exist, and there’s even one to two big Chinese companies. The two- and three-wheeler market combined with the telecom sector has the potential to create demand for up to five gigawatt per hour (GWh),” continued Chaudhry.

Sticking to just the two- and three-wheeler market, “the electric three-wheeler market is the most ripe market right. You can potentially convert a large proportion of the traditional three-wheelers to electric in a short span of time.” Arshad told Profit. “The challenge in the two-wheeler market is that almost 80% of two-wheelers are either CD-70s or replicas of it. That in itself is a problem because their price point is so low that you cannot offer a lithium-ion battery. The solution is that they may need to have different business models. Maybe, out of two wheelers, we can prioritise the commercial two wheelers first and maybe worry about the private two wheelers when the battery costs go down or we develop some new business model for supporting that. Commercial two wheelers is somewhere we can start and slowly and gradually it will have some inroads into the private two wheeler market as well.” Arshad continued.

Now what are the benefits of these sectors being operational at the same time as the batteries for cars are being exported? Economies of scale. “The technology at the cellular level is the same. The only thing that changes is the battery packs assembly. Cars need bigger packs. For bikes and rickshaws you need smaller packs. But the features are the same. So, basically with a slight modification in the existing setup, you can in the future also install packs for cars.”Chaudhry told Profit. Pakistan as a whole would benefit from allowing these spillovers to take place as they will largely be positive and bring down the cost of production. Any other benefits? Reduced moral hazard.

Once these two industries are sufficiently jolted, other potential sectors could also spring up. “In the next few years, you’ll see that the battery has other uses for example, in solar technology, grid storage, grid-free living, off- grid electrification. Storage will play a major role in all of these so it has uses beyond just electric vehicles.” Arshad tells Profit.

“The biggest challenge in the electric vehicle battery market is that when you try to sell on the international market, customers enquire about our domestic operations. They ask what is the scale at which we operate in our respective domestic market,” said Fahad Zaheer, Head of Marketing at Osaka Battery.

“If we export a product without having any local experience in it or without a local portfolio, then international customers will be hesitant in buying. After-sales is a significant element to the success of this. International customers would like/expect the assurance that they can receive a replacement battery or support from the company if the battery does not perform well. The easiest way to allay their fears is for a company to highlight their domestic portfolio, which demonstrates how the product will perform internationally based on domestic results,” Zaheer continued.

If you can have bakery owners become real estate and furniture tycoons then it is likely that whichever of our battery companies to set up as exporters will also be catering to these particular domestic markets Operating in”

“both provides the requisite domestic portfolio to reduce the search cost and hesitancy foreign customers may have. Who knew the seth model was so good at reducing moral hazard?

Pakistan’s current inability to double down due to financial limitations actually benefits us even. “Lithium-ion is an evolving technology. As soon as you start manufacturing a type of battery, maybe another slightly different technology evolves, and then you may have to change in your lines or whatever. So that is a challenge,” Arshad told Profit.

There’s actually three different kinds of batteries as well. “There are three designs for batteries: cylindrical, prismatic, and pouch. Tesla uses cylindrical batteries, whereas China’s BYD uses prismatic batteries. Selecting which battery design you want to manufacture is a science on its own.” Chaudhry explained to Profit. Now Chaudhry and Arshad’s statements might actually be advantageous to Pakistan.

Whichever company that does set up shop is unlikely to just pick one battery standard as it heightens their already very high-risk profile, simply due to operating in Pakistan. Therefore, slowly figuring out how we go about this and dipping our hands into as many pots as possible might actually lead Pakistan to picking the winning horse. Such a scenario would avoid ridiculous sunk costs for any company as well.

So, how do we achieve all of this in reality?

What will it take to get this off the ground?

“We need an EV policy framework for three areas: a policy for manufacturing two- and three-wheel electric vehicles, a policy for battery storage, and one for charging infrastructure. These are all interconnected. India has made three separate policies for all three, and we need to follow suit. We need one specific government department to draft it and offer a one-window solution,” Chaudhry said. Is that all? Sadly not.

This may jolt the domestic market but the government would still need a bespoke policy to somehow translate domestic gains into a positive spillover for exports. What complementary policies can it enact? “The first thing that is required is a framework in which you have investors because you have a lot of money involved. It’s a kind of technology transfer, and therefore, you need international partners.” Chaudhry told Profit. “China constitutes so much demand that you won’t be able to execute it without taking a Chinese partner on-board,” he continued.

However, as with the theme of this piece, it is easier said than done. “For larger companies, Pakistan is a low priority destination or less priority. They say we will go there after four to five years,” stated Arshad.

Now as much hate as the automotive companies get in Pakistan, the government is not really much better. Pakistan’s export processing zones for example, have not really taken off. The State Bank has made a report on its failings, however, that is beyond the scope of this article. Similarly, electric mobility is a key aspect of the Auto Industry Development and Export Policy 2021-26. However, all we’ve seen till now is subsequent government’s flip flopping between the duties levied on imported electric vehicles.

What ought to be the government’s role then? “The government has to take a major role. There have to be government-to-government agreements which at least ensure a supply chain of lithium cells and other byproducts. These are needed to establish the lithium-ion battery manufacturing industry in Pakistan.” Arshad told Profit. There also has to be less ambiguity as to whether a policy will hold beyond the tenure of the

government that drafts it.”

“The government’s policies keep changing. Before one policy can be implemented, another change or a policy is already on its way. That’s a very tricky situation for an investor who is investing in the technology and the R&D,” said Arshad. “If we have decided that we want to go into electric vehicles then we have to commit to it.

Irrespective of the changes in the government or the bureaucracy, we have to maintain this stance. The second there are too many cooks to make this meal it will spoil. An investor will not invest if the government itself is not clear about what it wants to achieve from a policy,” he added.

Assuming all relevant decision makers made this a bi-partisan commitment, would it work? The more important question, however, is what happens if we don’t try at all?

What happens if none of this manifests?

“Battery technology is evolving so if we become part of that battery value chain right now, we’ll have a chance to be part of the global value chain,” Arshad explained. “We are still thinking about it, whereas the world is moving in this direction with great speed. There’s already $500-600 billion worth of investment in the pipeline.” said Chaudhry. So a lot of money is on the table that we are potentially forsaking. So much forex to artificially prop our currency and other bad decisions. Hopefully that alone entices the government to look into it.

“If we repeat what we did with engines with batteries then we will be in the same situation in five years whereby the cars will be manufactured here and the batteries will be imported.” Arshad stated, adding “Pakistan has a 100 GWh requirement over the next 10 years in terms of its own battery needs. If we end up importing them from China then we will be adding a battery import bill to complement our oil import bill.”

There’s really no reason to not experiment, at least. Chapter 3 of the Export Processing Zone Authority Ordinance levies duties on products being sold in the domestic market by companies based within the zone. Similarly, Rule 5(2) of the Export Processing Rules (1981) disallows industries that compete with domestic exporters to operate in the Zone. These two in-effects provide the safeguard that the domestic automotive industry needs from this entire experiment. Furthermore, Rule 14 allows companies to earn rebates when they sell products to companies within the zone. This provides the opportune moment for our seth-based companies to set up shop inside and outside the zones and actually create synergies whilst catering to the domestic and export markets.

Furthemore, quardenning off the two markets in this way provides current automotive incumbents sufficient time to live out their hybrid vehicle dream. It also simultaneously provides them the reassurance that they will have access to some form of electric vehicle infrastructure when they do decide to pull the plug as well.

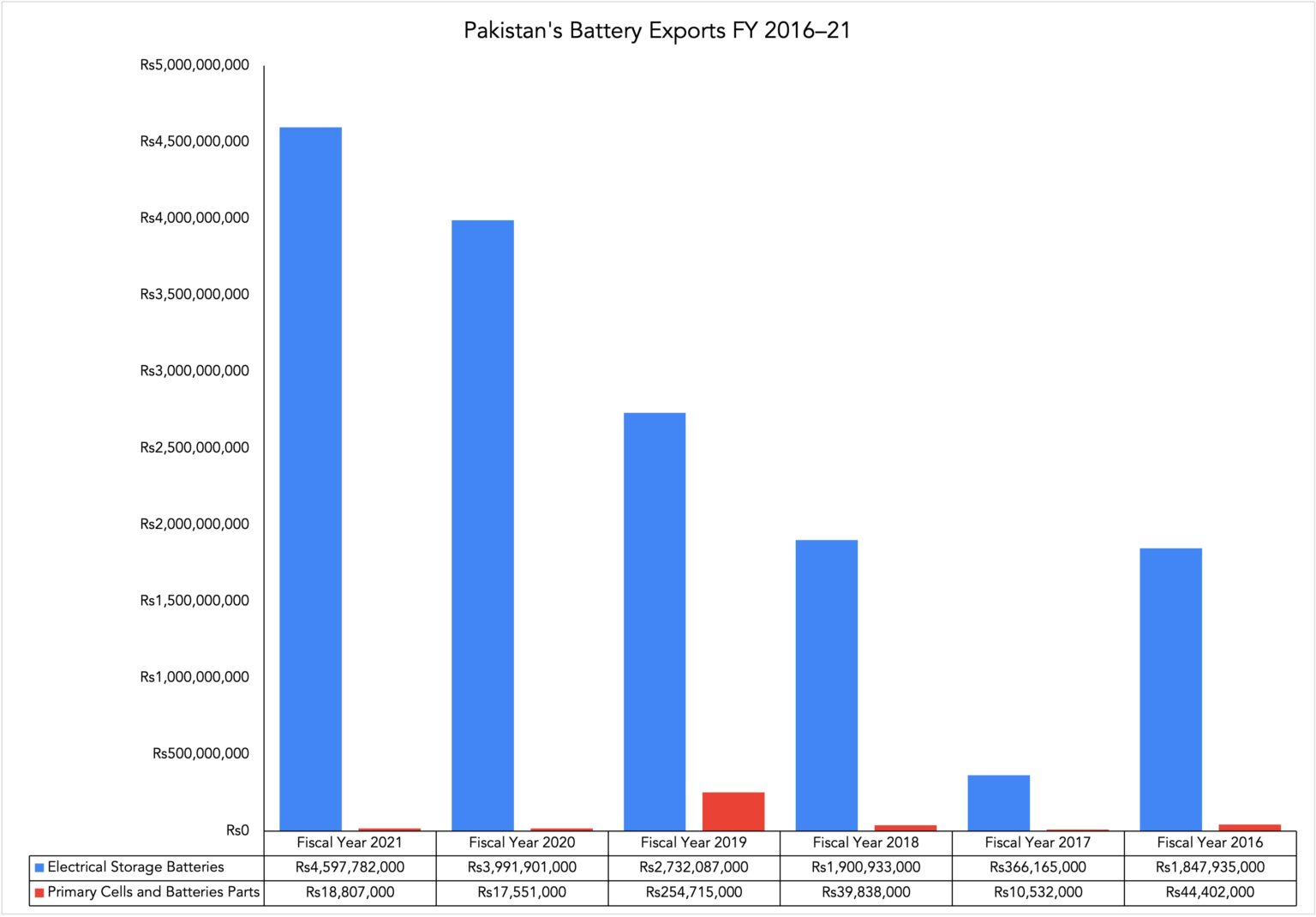

Finally, if nothing else, not doing this will be a double whammy for Pakistan. Looking at the State Bank’s export data, Pakistan has earnt Rs15 trillion from FY 2016–21 through battery related exports. On average Pakistan earnt Rs1.3 trillion per year in this time period, with the earnings increasing on average year-on-year. However, all of this is also about to come tumbling down very soon. Why? Well, this goes back to our current battery infrastructure being based on lead-acid technologies. “Lead-acid technology will eventually become outdated. It will be phased out globally, albeit at a slower rate in Pakistan,” Chaudhry said.

We import some of the inputs needed to build, so what is going to happen when we will no longer be able to export them? More balance of payment issues. The writing is on the wall already and in this week’s magazine edition.

The long-term prospects are not as bleak as one would imagine. Firstly, the only puzzle missing in Pakistan’s”

“mineral jenga is lithium. In the situation that the reserves are not significant at all, it is fine. They just have enough amounts to act as a catalyst for all of this. Whereas, if they do not then Pakistan can just import them from Afghanistan and benefit from the sheer proximity to the reserves. Peshawar-Kabul motorway ought to ring a bell here.

Secondly, the macroeconomists amongst us would raise the question, rightfully so, whether Pakistan’s economy could actually support such large scale imports. This is particularly important given our current forex conservation measures include the aforementioned CKD conundrum, and also previously included outright bans on imported vehicles. Well, Profit sought to answer this as well.

“If you are importing inputs to export finished goods then why not? There will be some level of value addition if the product is being exported,” Ayaz told Profit when asked whether our balance of payments could support such an endeavour. “If you import something worth Rs8 then you will sell it for Rs10, at least, if you want to export it. Right?” Thus, the endeavour can be viable if it’s solely export oriented.

What are we left with then? “I think we are just waiting for one or two success stories. If that happens, I think many of the companies will be jumping on it,” Arshad stated. The entire situation is akin to a game of jenga where everything has to be carefully built piece by piece. The only thing is if it is not built then we are going to have much of the same industrial problems we already have, but for much much longer.”